Polls unmask the state of kayfabe in Japanese and American pro wrestling

The divide between fans and non-fans of pro wrestling has always been enormous. Whether the issue is why a person would like to watch this form of entertainment to the very nature of the art form itself, fans and non-fans have rarely seen eye to eye even in America. As it turns out, we now have polling data to show that the same divide exists in Japan, where wrestling is anecdotally shown more respect and given serious coverage in their mainstream media.

In the United States, there is usually a culture and class conflict between those who watch pro wrestling and those who dislike it, or even look down upon it, as a form of entertainment. It's common for non-fans in America to ridicule fans under the erroneous assumption that fans are simply too stupid to understand they are watching performances with predetermined outcomes. A confrontational non-fan (read: on the internet or in their teens) would proudly declare, "it's fake!" In person, it would be accompanied by a smirk, believing it's remotely clever and somehow revealing shocking new information to a fan. That same non-fan would then proceed to watch their favorite scripted movie or reality TV competition show, without the slightest sense of irony or self-awareness.

One major difference in the cultural context of pro wrestling in Japan is that non-fans tend to be more respectful of this form of entertainment, even if they are not personally interested in watching it. While it would be convenient to argue that the serious presentations of organizations like All Japan Pro Wrestling was the cause of this - especially as it was the top promotion of the 1990s - keep in mind that comedy matches and "garbage wrestling" (a bloody style emulated by ECW and other independent promotions since the 1990s, known as "hardcore wrestling" in the west) coexisted in the same period. Nevertheless, it's common to find Japanese sports media coverage of major wrestling events exhibiting the same level of respect for it as a baseball game.

Some American fans of Puroresu, and even a few American wrestlers who have worked in Japan, believe that Japanese fans and media treat pro wrestling so respectfully because kayfabe (a term referring to maintaining the narrative of the characters) had never been broken in Japan as it had been in the United States in the late 20th century. In reality, it's far more likely that these Americans simply happened to encounter the same type of in-story interaction as comic book fans (or actors and actresses starring in Marvel movies) debating the merits of different heroes and villains within the context of the story.

In fact, in 1985, four years before WWF (now WWE) owner Vince McMahon first broke kayfabe by declaring his organization's product "sports entertainment" to avoid paying Athletic Commission and state regulator fees, Satoru Sayama - famous in Japan for having wrestled as the original Tiger Mask - wrote and published a Japanese book entitled "Kayfabe" exposing the inner workings of the business. Less than a decade later, pro wrestlers Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki founded Pancrase, the first Mixed Martial Arts promotion predating the UFC and PRIDE. Pancrase was launched with the concept of promoting "shoot" (competitive) fights with no predetermined outcomes - a concept that only makes sense in contrast to an acknowledged truth about the founders' occupation as pro wrestlers. And, of course, the WWE is among the promotions that Japanese fans watch, as were its predecessor entities, the WWF and WCW in the 1990s. Neither culture exists in isolation, but Americans in the post-WWII era have been standing high up on the world stage, squinting through spotlights that nearly blind them from the audience, while other cultures often see Americans clearly up on a pedestal.

From July to September 2012, sociology professor Fumihiko Saito polled wrestling fans at the exits of multiple event venues in Tokyo. The questionnaire was presented to fans who attended a World Wonder Ring STARDOM show at Shin-Kiba 1st Ring in July, a Pro Wrestling NOAH show at Ryogoku Kokugikan in July, a New Japan Pro Wrestling show at Korakuen Hall in August, a STARDOM show at Korakuen Hall in August, a WWE Japan show at Ryogoku Kokugikan in August, a NOAH show at Korakuen Hall in August, an All Japan Pro Wrestling show at Ota Ward Gymnasium in August, a Wrestling New Classic show at Korakuen Hall in August, a Michinoku Pro show at Korakuen Hall in August, and a UWF show at Koenji in September. Saito also rounded out her study with a sample of people of non-fans of wrestling, taken from a university class on Subculture Theory I who had answered "no" to the question, "Are you a fan of professional wrestling?"

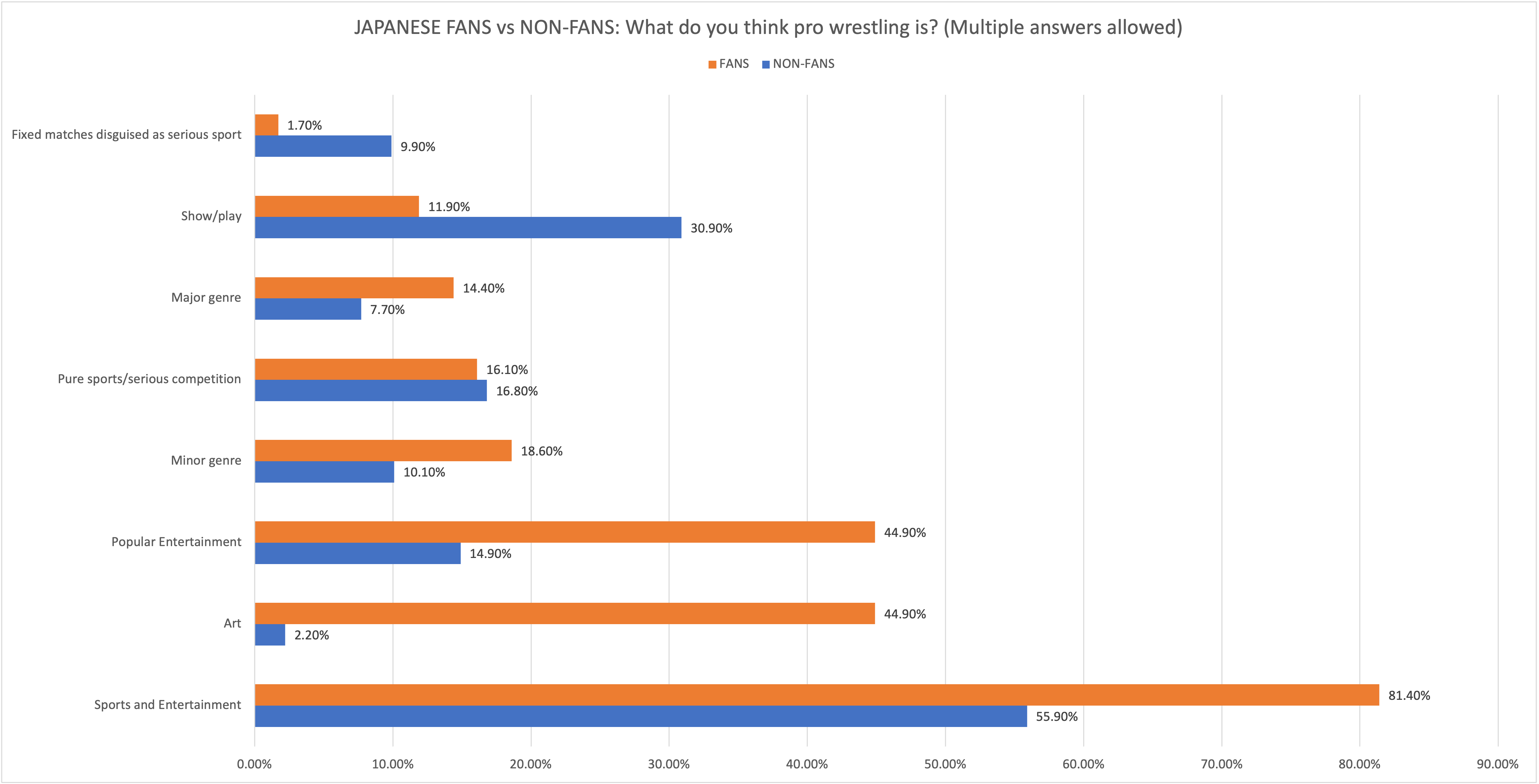

With fans and non-fans clearly divided into two separate groups, Saito asked, "What do you feel pro wrestling is?" (Multiple answers were allowed, so the totals don't add up to 100% on either side. Instead, each respondent was able to choose as many answers as they felt applies to their personal viewpoint of pro wrestling.)

81.4% of fans chose "sports and entertainment" compared to 55.9% of non-fans. The non-fans who see pro wrestling as sports and entertainment still forms a majority, just not quite as solid of a majority as in the case of fans.

Likewise, only 1.7% of fans would label pro wrestling as "fixed matches disguised as a serious sport" while 9.9% of non-fans did. The difference is not surprising since it's more likely for a non-fan to agree with a statement with such a negative connotation. More importantly, both are in sync as this statement was the least chosen option, whether for fans or non-fans. This is less a declaration of whether each respondent viewed wrestling as legitimate and more a statement that implies wrestling actively pretends to be a competitive sport.

More revealing is that "pure sports/serious competition" was chosen by only 16.1% of fans and 16.8% of non-fans.

The remaining options mainly demonstrate the cultural clash between fans and non-fans, with 44.9% of fans who thought of pro wrestling as "art" while only 2.2% of non-fans did. Likewise, 44.9% of fans also thought of pro wrestling as "popular entertainment" while only 14.9% of non-fans agreed. "Art" and "popular entertainment" showed the largest contrast between how fans and non-fans regarded pro wrestling while, oddly enough, the viewpoint of wrestling as a "show/play" was reversed with 11.9% of fans and 30.9% of non-fans.

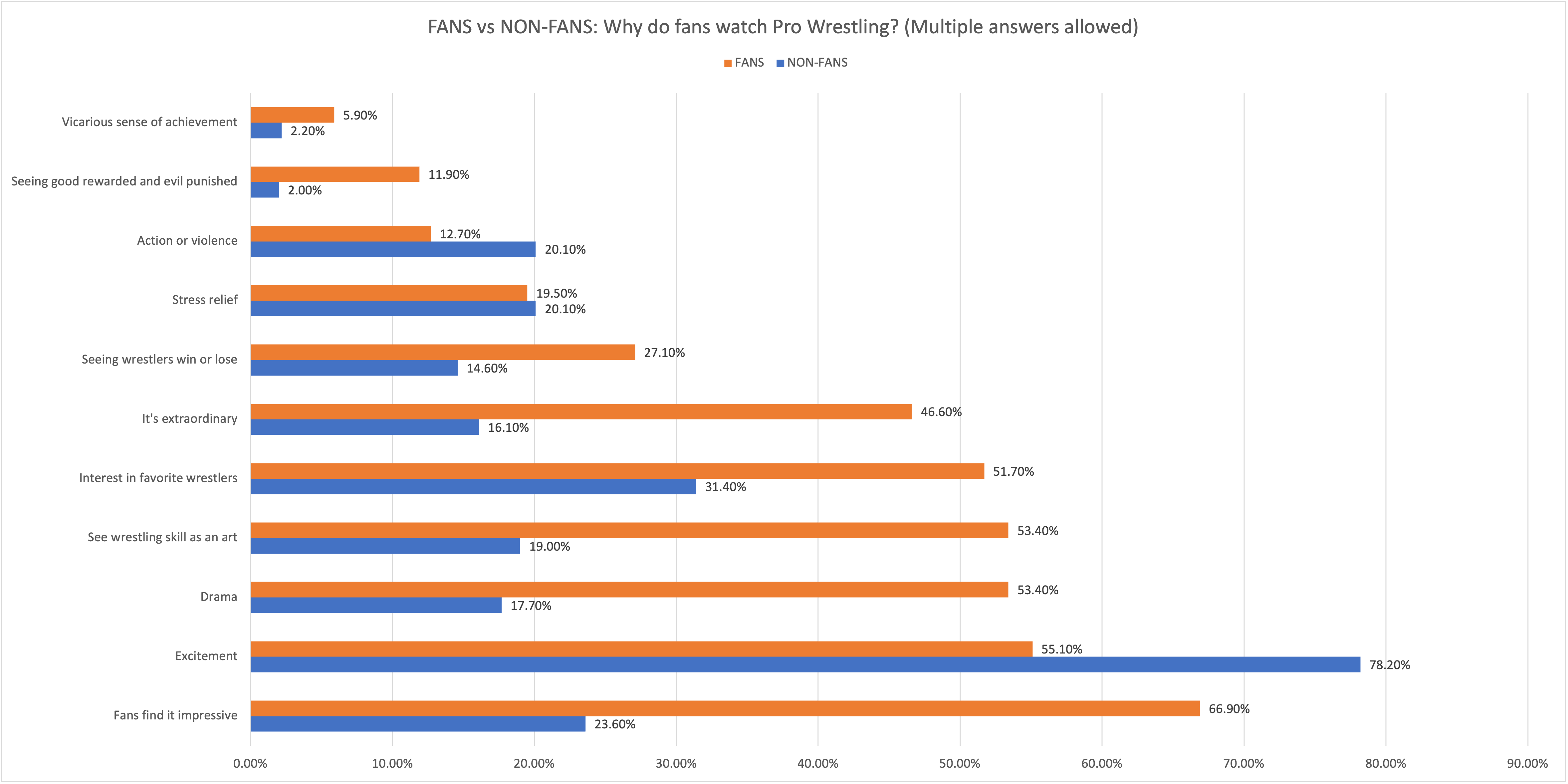

Fans and non-fans were asked, "Why do you think fans watch pro wrestling?"

The biggest difference between fans and non-fans for this one was that fans overwhelmingly felt that fans (presumably including themselves) choose to watch wrestling because it's "impressive" at 66.9% while only 23.6% of non-fans felt this would be the reason. Likewise, 53.4% of fans felt fans view wrestling is an art while only 19.0% of non-fans, somewhat unsurprisingly, believed this to be a factor. And 53.4% of fans also felt fans watch wrestling for drama while only 17.7% of non-fans believed so.

On the opposite end, most non-fans (78.2%) believed fans watch it for "excitement" while only 55.1% of actual fans agreed. Along the same lines on non-fan misconceptions, 20.1% of non-fans believed that fans watch wrestling for action and violence while only 12.7% of fans felt the same way. Perhaps more significantly, neither fans nor non-fans reached a majority that felt this was the reason for watching pro wrestling.

It's not surprising that larger numbers of non-fans would perceive pro wrestling in ways that equate to shallow connotations like the belief that people watch it for action and excitement, while fans view it as an art.

What's less obvious without polling data is that the Japanese view of pro wrestling, whether in the eyes of fans or non-fans, seem to form on strong consensus that pro wrestling is "sports and entertainment" (81.4% of fans, 55.9% of non-fans) and, by a wide margin, not "pure sports/serious competition" (with only 16.1% of fans and 16.8% of non-fans believing it is.)

This reveals that over 83% of Japanese, both fans and non-fans, do not view pro wrestling as a serious competitive sport, and yet, the fans remain fans - an important theme to keep in mind. It's also one of the few agreements between fans and non-fans, apparently.

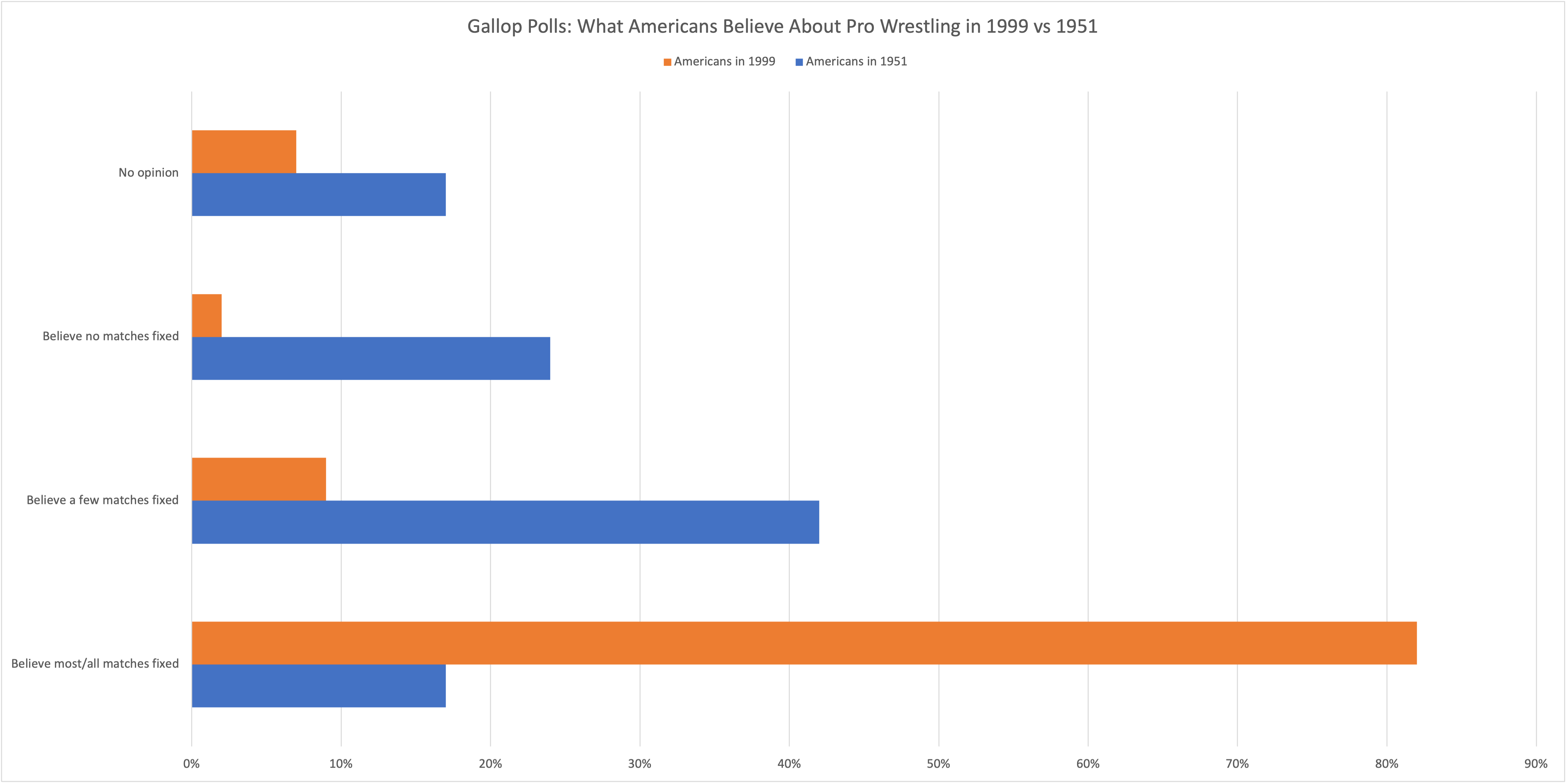

For comparison, there isn't a lot of polling data of Americans, whether of fans or non-fans, about pro wrestling in the west. Of the few polls that have been conducted, Gallop collected responses from Americans in 1951 and 1999.

When Americans were polled in 1951, only 17% believed that most or all pro wrestling matches had predetermined outcomes. 42% believed "a few" matches were fixed, 24% believed none were fixed, and the remainder had no opinion either way.

In 1999, at the peak of the Monday Night Wars between the WWF and WCW, battling for cable TV ratings supremacy every week - in a time where Degeneration X and nWo t-shirts (representing the most popular stables in each organization respectively) were seen everywhere across North America - the numbers had nearly reversed. 82% believed "most or all" pro wrestling matches have predetermined outcomes, only 9% believed that merely "a few" are fixed, and those who believed that no matches are ever fixed had dropped to a measly 2%.

While the Japanese polls are from 2012 and the American polls are over two decades old, there's no reason to believe fans would trend in the opposite direction since. After all, present day fans live in a time after the release of American films like "The Wrestler" and "Fighting With My Family", TV shows like "Heels" and "GLOW", and the Japanese film "My Dad is a Heel Wrestler" about a boy who discovers that his father is a heel wrestling for NJPW.

Even wrestling video games, which have long stuck to the kayfabe universe of players controlling characters who are only trying to win, have evolved with the culture. Fire Pro Wrestling World encourages players to maximize the entertainment value of the match for in-game audiences rather than simply trying to win. Fire Pro Wrestling is a series of Japanese wrestling video games once entirely un-licensed to use the likenesses of any real-life wrestlers and only narrowly escaped legal action in its early decades by changing names of both Japanese and American wrestlers, while being arguably more accurate than many of the licensed games. The series has undeniably come into the Japanese wrestling fandom mainstream as Fire Pro Wrestling World is officially licensed to use wrestlers from NJPW and STARDOM.

In both Japan and the United States, polls have demonstrated that wrestling fans are still wrestling fans even when they believe the results are predetermined. When Japanese wrestlers maintain kayfabe in domestic media coverage and on social media, it's fun for everyone involved but it's not a critical requirement for the continuity of the business, whether in terms of growth within Japan or expansion into other countries. Decades after the original Tiger Mask exposed the business and Vince McMahon declared his company to be "sports entertainment", fans on both sides of the Pacific continue to buy tickets and merchandise, and watch pay-per-view events and TV shows, from their favorite wrestling promotions.

After all, wrestling fans enjoy everything from comedy bouts and "garbage" or "hardcore" wrestling to hour-long exhibits of fighting spirit, just as moviegoers enjoy films that range from comedy and action blockbusters to Oscar-bait drama. We would all agree that first responders deserve our respect for doing the real thing, but most audiences would prefer a film that accurately captures their experience over security camera footage of an anticlimactic incident where real people get hurt.

Looking at it this way, a "smark" wrestling fan understands they are witnessing a well-crafted narrative about a character embodying a surprisingly accurate analogy to the real-life struggles we all face. And they're still a fan.